In the third part of our series on Illinois Gambling Crime history, we will be focusing on some key individuals, locations, and occurrences that played a significant role in shaping the early years of gambling in the state.

Continue reading to learn about corrupt politicians, a famous gala, and a floating casino.

MEET CHICAGO’S FIRST CRIME LORD, MICHAEL MCDONALD, IN OUR FIRST IGH INSTALLMENT

The Lords of The Levee

Chicago had gained a reputation for questionable morals by the late 19th century, in part because of activities occurring in the city’s First Ward.

The First Ward in Chicago is known for being the hub of the city’s central business district and crime activities. The elevated rail system that was constructed at the turn of the century in this area was so lucrative that it earned the First Ward the nickname of “world’s richest.” The loop of the rail system also gave its name to the neighborhood, which included a notorious 4-block redlight district known as the Levee.

Similar to numerous frontier towns, the redlight district derived its name from the adjacent docks. As expected, brothels, saloons, dance halls, and gambling establishments flourished in the vice-laden neighborhood.

The illegal success of the First Ward was largely attributed to the corrupt influence of aldermen John “Bathhouse” Coughlin and Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna, who held power in the ward for a significant portion of the early 20th century.

Coughlin and Kenna were able to profit significantly from the flourishing gambling and vice under their protection, earning them the nickname “Lords of the Levee.” In turn, the Levee brought in a substantial amount of money for the pair.

It has been reported that the councilors collected over $15 million in protection fees from the Levee’s closure in the early 1910s. Adjusted for inflation, that amount would be approximately $451,533,333.33 in today’s currency. This represents a significant sum of money.

The pair was also involved in the Gray Wolves, a larger organization of dishonest aldermen who accepted bribes in exchange for city contracts. McClure’s Magazine initially dubbed the group wolves due to “the color of their hair and the predatory cunning and greed of their personalities.”

However, by the mid-1920s, the influence of the pair began to decline with the emergence of mobsters Johnny Torrio and Al Capone. Luckily, Capone developed a fondness for the “Lords” due to their unwavering loyalty to Torrio and his predecessor, Jim Colosimo.

Stay tuned for more information on the trio in an upcoming episode. In the meantime, continue reading to learn more about each of our “Lords.”

GET TO KNOW MONT TENNES, US RACE WIRE CZAR, IN PART 2

John “Bathhouse” Coughlin

John Joseph Coughlin was born in Chicago in 1860, and his family faced financial hardship following the destruction of their grocery store in the Great Chicago Fire.

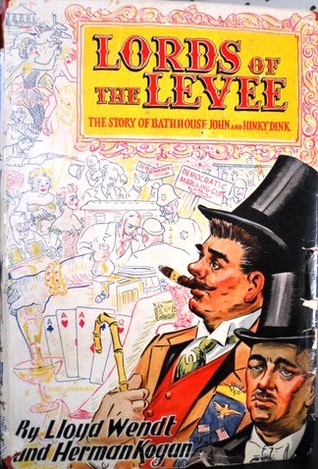

Coughlin Jr., on the other hand, showed little concern for the difficulties that followed. As noted by Lloyd Wendt and Herman Kogan in their book about the Lords, Coughlin reportedly stated:

I never cared about money. I’m grateful that the fire destroyed the store. Without that happening, I might have been born into wealth and attended Yale, never achieving anything meaningful.

Instead of taking the easy route, Coughlin chose to carve out his own distinct path, eventually earning the nickname of a bathhouse masseuse. However, in a short amount of time, he was able to own both a saloon and multiple bathhouses.

In 1892, despite his lack of political experience, Coughlin was elected as a representative for Chicago’s First Ward. This marked the beginning of a 50-year political career that only ended with his death. Coughlin became Chicago’s longest-serving alderman, a title he held until 2014 when Edward Burke from the 14th ward surpassed his record.

Apart from his political career, Coughlin gained attention for his eccentric fashion sense, questionable poetry, and love for horse racing. He found initial success in the latter interest, but eventually faced financial struggles and died in poverty in 1938.

In a 2012 NBC news retrospective, Coughlin was ranked as the third most corrupt official in Illinois history, while his friend and partner-in-crime, Kenna, came in fourth in the corruption rankings.

Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna

Born in 1857, Michael Kenna entered the world at the intersection of Polk and Sholto (now Carpenter) streets in Chicago’s New West Side neighborhood.

He left school at age 10 to sell newspapers. At 12, Kenna, now an orphan, borrowed $50 to purchase a newsstand. The stand was very profitable, allowing him to repay the loan in just a few weeks. McKenna operated the newsstand until 1877.

Legend has it that during this period, Chicago Tribune publisher Joseph Medill began referring to Kenna as “Hinky Dink.” Kenna professed not to know the reason behind the nickname, but when pressed, he suggested it was related to his playful behavior at the swimming hole. However, Kenna was only a diminutive 5’4″ in stature.

Kenna worked at a newspaper in Leadville, Colorado before returning to Chicago to open a saloon called The Workmen’s Exchange. He traded meals for votes from the less fortunate, and by 1882, his establishment was thriving. This success led to his involvement in the local democratic organization, solidifying his place in the community.

Kenna and Coughlin initially met during this period, but their friendship didn’t develop until later. However, by 1893, they had formed a strong alliance. Coughlin, who was already serving as an alderman, took on the role of the public figure, while Kenna operated more discreetly in the background.

Despite losing his first run in 1895, Kenna later joined Coughlin as First Ward alderman in 1897. He served as an alderman alongside Coughlin until 1923, when the Illinois General Assembly reduced the number of councilors per ward from two to one. Kenna, who was not fond of council meetings, decided to step down. However, he made a return to public service from 1939 to 1943, being elected unopposed to fill Coughlin’s seat after his passing.

Kenna, who passed away in 1946 at the Blackstone Hotel due to diabetes and myocarditis, was a wealthy individual. He had allocated $33,000 ($504,328 today) for the construction of his mausoleum, but his heirs engaged in a dispute over his estate, resulting in the disappearance of the funds. Consequently, Kenna’s grave is now adorned with a simple $85 ($1,299) headstone instead of the intended mausoleum.

The First Ward Ball

The infamous First Ward Ball was a yearly political event organized by Chicago’s beloved Levee Lords, John Coughlin and Michael Kenna, as a fundraiser.

It is said that the extravagant event was created as a way to ensure steady cash flow for other activities, such as funding bribes and covering expenses for police protection. The idea for the event came from a successful fundraiser for a disabled musician in the community, even though it was recently shut down by authorities.

In the past, charity parties were known for their peaceful atmosphere, with police officers being welcomed as esteemed guests. However, a confrontation between attending officers at the 1895 fundraiser sparked public outrage and ultimately led to the event’s cancellation.

After the cancellation, Coughlin suggested that they host a similar event for their own benefit. While Kenna was hesitant, he still backed Coughlin’s idea. The First Ward Ball was then launched the next year.

Suppliers discounted beer, wine, and spirits in response to the invitations being sent out. Service staff were so confident in receiving generous tips that they paid $5 in order to work at the event.

First Ward Ball begins like a lion, ends like a lamb

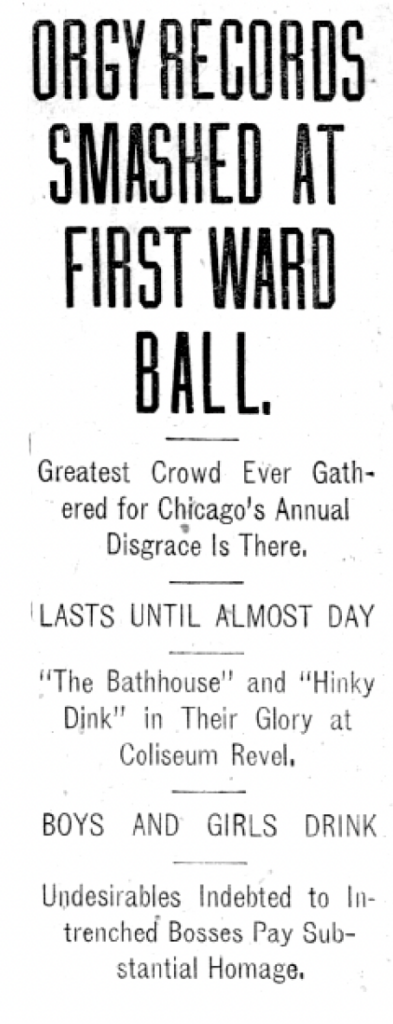

The 1986 ball drew in a mix of society thrill seekers, police captains, politicians, prostitutes, and gamblers, as reported by the Chicago Tribune.

It is said that Coughlin began the grand march accompanied by the well-known Everleigh sisters. Minna and Ada were the owners of the prestigious Everleigh Club, a luxurious brothel in the Levee district. Witnesses describe his entrance as grand, wearing an extravagant green dress suit paired with a mauve vest, pink gloves, a silken top hat, and yellow pumps.

According to most reports, the inaugural First Ward Ball was a resounding success.

The party quickly outgrew its original location at the 7th Regiment Armoury and had to move to the Chicago Coliseum to accommodate the growing number of attendees. At its height, the ball attracted ten to 20 thousand guests and raised as much as $50,000 each year for the councilors.

However, by 1908, the ball had gained such a bad reputation that newspapers throughout America were reporting on its scandalous immorality.

According to reports, in that year, party-goers consumed 40,000 quarts of champagne and beer while unruly individuals stripped clothes from unattended women. Local madam French Annie went as far as stabbing her boyfriend with a hat pin, although the reason behind the attack was not disclosed.

The city revoked the ball’s liquor license just weeks before the 1909 extravaganza, prompting Coughlin to write his shortest poem.

“No Ball; That’s All.”

Coughlin and Kenna opted for a more subdued concert for the last year of the “Ball,” eschewing the typical alcohol-fueled festivities. As expected, the alcohol-free event drew a smaller crowd of approximately 2,500 attendees, a stark contrast to previous years. Instead of the usual lively march, guests were treated to a performance by a classical orchestra while seated in wooden chairs affixed to the coliseum floor.

The First Ward Ball ended for good when it closed its doors at 11 p.m. that night.

The City of Traverse

Contrary to its deceptive name, the City of Traverse was not a city; it was actually a freight and passenger vessel constructed in Ohio in 1871.

The oak-hulled ship operated as a passenger and cargo vessel between Chicago and Traverse City, Michigan for 35 years. In 1905, it was transformed into a floating gambling house, managed by Chicago bookmakers Bud White, Harry Perry, and Charles “Social” Smith. To avoid legal issues, the ship only accepted bets once it was outside of Illinois waters and beyond the reach of state authorities.

The City of Traverse made history as the first ship in the United States dedicated solely to gambling. When it set sail from Whiting, Indiana, it could carry between 200 and 800 men who would place bets on horse races.

On the first day, the Chicago Tribune noted that the people of Chicago had been given a practical chance to spend their money by throwing it into the lake.

The boat operators successfully avoided Chicago police for almost three years, as the authorities had limited legal options while the boat was in the water. Nevertheless, Chicago officials persisted in their efforts to immobilize the vessel.

Despite grand plans, police fail to ground gambling boat

The operators of the CoT were fortunate that Indiana’s Governor, J. Frank Hanley, held a highly conservative viewpoint but also believed in the autonomy of jurisdictions. Despite his disapproval of Chicago bookmakers profiting in Indiana, he believed it was not the state’s responsibility to confront them, leaving any challenges to be dealt with by Chicago authorities.

In 1907, the police in Chicago changed their strategy by going undercover, boarding the ship, and collecting evidence. They then waited for the boat to dock in Chicago before arresting the gamblers.

The police’s plans were foiled when the bookmakers arranged for tugboats to transport the gamblers to shore in Whiting and Indiana Harbor. The players then made their way back to Chicago via train.

In anticipation of the tugs landing in Indiana, police planned to follow and arrest bettors as soon as they crossed the Illinois state line.

Although the plan caused a commotion on Whitting’s beach, only six people were arrested. Despite this success, bookmakers intended to increase their fleet of tugboats to maintain the operation of the gambling haven. However, less than two weeks later, the City of Traverse ceased its operations, leading to a change in the plans.

After a few weeks, the boat resumed its normal activities of transporting passengers and fruit across the lake from Michigan to Chicago. However, after operating on the water for almost three years, the City of Traverse made history as the first fully-fledged gambling boat in the United States.