Go directly to the content

In the fourth part of our series on the history of gambling in Illinois, we introduce you to John “Mushmouth” Johnson, the African American gambling mogul of Chicago.

Although he started from humble beginnings, Johnson managed to amass a significant fortune through his vice-related activities. This wealth continued to support Black businesses and culture in Chicago even after his passing.

PART 1: MICHAEL MCDONALD, CHICAGO’S FIRST CRIME LORD

John “Mushmouth” Johnson

Multiple sources indicate that John V. “Mushmouth” Johnson was born in St. Louis, Missouri, in either 1856 or 1857 to Ellen and John Sr.

According to some reports, Ellen was a nurse who once attended to Mary Todd Lincoln. However, other records describe her simply as a homemaker. Despite the differing accounts, Johnson maintained a close relationship with her throughout his life.

Regrettably, there is limited information available about Johnson’s early years. Nevertheless, it is known that he relocated from his hometown of St. Louis to Chicago at a relatively young age.

Johnson also had a younger brother named Albert, who passed away in 1890 at the age of around 30. His younger sister, Eudora, was not born until 1871 but played a vital role in shaping Johnson’s posthumous legacy. More information about her will be shared soon.

There are conflicting stories about the origin of Johnson’s nickname “Mushmouth.” Some believe it was because of his use of strong language, while others say it was due to a speech impediment he had as a child. Regardless of the reason, the nickname reflects his lack of acceptance in high society. (Spoiler: He was not considered genteel.)

Johnson later remembered, “I didn’t really focus on academics. I preferred to explore where the real wealth was made. Some people who know me claim that I succeeded in finding it.”

When Johnson became a partner in the Frontenac Club, it was a clear sign of his success. However, it was rare for a person of color to have ownership in a prestigious establishment like this, a fact that was evident throughout his life.

PART 2: MONT TENNES, RACE WIRE CZAR

From nickels and dimes to Chicago policy king

Johnson began his career as a porter in a Chicago gambling house owned by white individuals around the year 1882.

During his time there, the fast learner meticulously analyzed the business operations and quickly moved on to managing his own nickel-gambling establishment.

In 1890, Johnson sold his first business and bought The Emporium, a saloon on South State Street. This marked the beginning of his involvement in real estate and became the hub of his gambling operations until his death in 1907.

The Emporium was truly a remarkable sight, with its three stories embodying the trendy Gay Nineties style of the era. The venue was adorned with intricate chandeliers and a bar made from luxurious Honduran mahogany. The decade was marked by decadent art, the clever words of figures like Oscar Wilde, the emergence of public scandals, and the beginning of the suffragette movement, all signaling the end of the Gilded Age.

In keeping with its distinctive style, Johnson’s Emporium featured three tiers of entertainment. The first floor was dominated by billiards, while craps and roulette took center stage on the second level. The third floor was dedicated to poker, with a bar serving up whiskey, gin, and beer as the preferred libations.

During that period, South State Street, commonly referred to as Whiskey Row, gained a notorious reputation for incidents such as Mickey Finn’s drug-fueled robberies of patrons at the Lone Star Saloon. However, Johnson’s establishment managed to maintain a relatively respectable reputation.

Policy played vital economic role advancing Black society

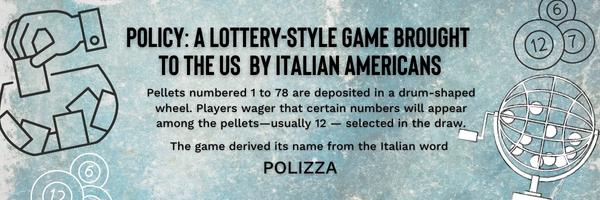

Despite that, Johnson’s focus was not solely on The Emporium. He was also heavily involved in Chicago’s policy racket.

In the well-liked game resembling a lottery, bets could range from a mere penny to a potential payout of 100-1. It comes as no surprise that the game resonated with those of limited means. While some criticized the game as exploitative, others argued that it played a crucial role in the progression of black society.

Nathan Thompson, author of Kings: The True Story of Chicago’s Policy Kings and Numbers Racketeers, stated that policy served as the economic engine driving the advancement of the black community.

Numerous jobs were necessary to support the game, and policy supported numerous businesses and institutions in the community, including black hospitals, banks, insurance companies, mom-and-pop grocery stores, political careers, and law careers.

Given Johnson’s limited formal education and lack of access to generational wealth, the policy business presented an opportunity for success. As he was quoted in the Chicago Tribune, he questioned, “What other options are available for a person of color like me?”

PART 3: FIRST WARD LEVEE LORDS, A DEBAUCHEROUS BALL AND FLOATING GAMBLING HAVEN

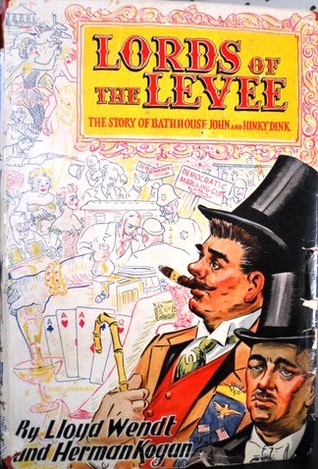

Mushmouth Johnson and the Lords of the Levee

The Emporium and Whiskey Row were located in the notorious First Ward of Chicago known for its high levels of vice.

During that period, alderman John Coughlin, also known as “Bathhouse,” and Mike Kenna, known as “Hinky Dink,” were in control of the troubled ward. Referred to as the “Levee Lords,” they were part of a corrupt group of aldermen called the Gray Wolves. Working together, they ran gambling establishments, bought votes, and manipulated public service contracts for their own benefit.

In order to thrive in the First Ward, it was necessary to maintain good relations with the Lords, and Johnson was determined to come out on top.

According to the Chicago Inter Ocean, in the 1894 First Ward elections, gamblers were actively participating and using money to buy votes.

Johnson was informed that he needed to secure 100 votes from people of color in his precinct or else he would have to shut down his establishment.

As time went on, Johnson’s ties to Chicago’s political machine grew stronger. He soon began receiving $150 a week from Chinatown’s gambling establishments in exchange for police protection. He also paid additional money for his own safety, which was given to the Lords and Wolves. Johnson even stated that he had to pay $4 in bribes for every dollar he earned.

Simultaneously, finding dependable protection was becoming increasingly difficult.

Mayor Carter Harrison Jr. was being urged by reformers to overhaul Chicago’s vice districts. Despite frequently boasting about his accomplishments, many felt that his efforts were lackluster.

Despite busting a group of high-profile gamblers in 1903, the Inter Ocean pointed out the hypocrisy.

These men were poor ten years ago, but have since accumulated the majority of their money during Mayor Harrison’s ‘reform’ administration.

Although it is accurate that Harrison ordered the police to raid saloons such as the Emporium, these actions were primarily for show rather than for any significant impact.

Change only began to occur when a citizen association strongly urged city hall. The outcome of their lobbying efforts would have negative impacts on the saloons and parlors of Whiskey Row.

1903 proved a tough year for Johnson

In 1903, Johnson made a promising start by purchasing the building across from the Emporium for $40,000, which would be equivalent to $1,354,600 in today’s currency.

In the end, Johnson’s primary source of wealth came from investing in real estate. He proudly stated, “I purchased a piece of land in an empty prairie that later became a thriving town.”

However, 1903 turned out to be an exceptionally unlucky year in Johnson’s tumultuous and hectic life.

The beginning of it all can be traced back to a gambler known as Thomas Hawkins.

Johnson had dealt with disgruntled customers before, including being shot by a dissatisfied man in 1896. However, in Hawkins, he faced a particularly relentless adversary.

The duo first disagreed over an $18.75 wager that Hawkins insisted he had won, but Johnson refused to pay.

It is unknown which hustler was telling the truth, but the quarrel between Hawkins and Mushmouth escalated when Hawkins struck Mushmouth in the face, breaking his glasses. The shattered lens shards flew into Johnson’s eyes, putting his sight at risk. Luckily, Johnson was able to recover.

Out of fear of revenge, Hawkins decided to cooperate with the police as an informant, resulting in a raid on the Emporium. In under a day following the operation, Moses Love shot Hawkins, injuring his arm and torso.

Hawkins managed to survive the attack and accused Johnson of orchestrating it, but the accusation did not hold.

Hawkins turned State against The Emporium

Although the kerfuffle may have calmed down, the citizens’ group persisted in urging the mayor to launch an investigation. Following the shooting, Hawkins chose to cooperate with the authorities and provide testimony regarding illegal gambling activities at the Emporium.

Johnson must have sensed the State’s presence looming closer as he openly spoke to the Chicago Tribune, vehemently denying the accusations.

We used to have some gambling going on here, but now there’s so much dust upstairs it’s an inch thick.

Regrettably, Johnson had not closed the saloon for the interview, resulting in a packed Emporium with customers that afternoon.

Still, Johnson insisted:

You can’t base your judgement on this alone. The rest of the week will be just as quiet and still.

Johnson’s saloon license was revoked by the city two days after the interview.

Despite the continued community pressure, the committee relaxed its efforts as Mayor Harrison seethed behind the scenes.

Regrettably, the Emporium had already shouldered the blame for the First Ward. The Inter Ocean reported that Johnson was deemed a political sacrifice while the more influential individuals escaped unscathed.

Despite facing that setback, Johnson quickly recovered and found success.

Shortly after the economic downturn, the city was faced with more significant challenges, particularly the tragic Iroquois Theatre fire that claimed the lives of over six hundred people. (To this day, it stands as the deadliest single-building fire in US history.)

The mayor of Chicago became embroiled in an international scandal after fire inspectors failed to address Iroquois building code violations.

Johnson’s luck turned around as the city was preoccupied, and the Emporium was once again thriving.

Retirement announcement triggered racial scandal

In 1907, Johnson announced his retirement and bid farewell to Chicago during an interview.

In the article, Johnson stated that he now only possessed a small portion of his former wealth. Despite this, he intended to use what little he had left to fund a trip around the world.

“You’ll hear from me in Africa playing dice,” he said. Little did Johnson know the trouble his interview would soon cause.

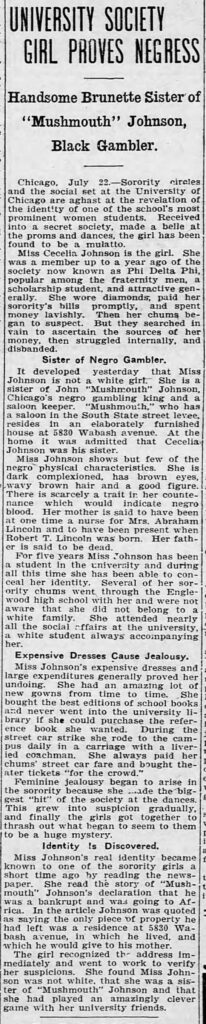

On July 27, 1907, headlines across the nation proclaimed: “University Society Girl Confirmed as African American.”

Johnson’s sister, Cecilia, was studying history at the University of Chicago at the time. She was intelligent, glamorous, intensely charismatic, and a member of Phi Delta Phi. Cecilia always had the most up-to-date school textbooks and rode in a carriage with a liveried coachman during the city’s streetcar strike.

Sorority sisters outraged

The issue was that no one at the university was aware of her race. Despite never trying to conceal her identity, she seamlessly navigated through white society.

Yet, the sorority papers reported that jealousy among the women was sparked by Cecilia’s wealth and popularity as the standout at social events.

Her Phi Delta Phi sisters were driven by jealousy to investigate further. One of them noticed Cecilia’s address mentioned in an interview conducted at Johnson’s home on Wabash Avenue. To make matters worse, Cecilia was not only Black but also the sister of a vice-peddler, and her education was funded by “tainted money.”

Her sorority sisters were filled with outrage.

One person stated, “We never once suspected she had colored blood in her veins.” Another person said, “If it weren’t for her color, I would gladly accept her into my sorority.”

Johnson expressed his public disdain for the scandal, stating that Cecilia’s “exposure” only highlighted the habits of Chicago. He expressed satisfaction at the humiliation felt by the city.

In private, he saw his sister as the most brilliant and beautiful presence in his life. The racism that drove Cecilia away from academia devastated Johnson.

A few months later, in September, Johnson caught pneumonia while traveling from Atlantic City to Kentucky and passed away on the train.

A large gathering of mourners, including family, friends, business associates, and even Police Inspector John Wheeler, gathered at Chicago’s Institutional AME Church to pay their respects at his funeral.

Contrary to previous assertions of being nearly impoverished, Chicago’s Black Gambling King is said to have amassed a $250,000 fortune (equivalent to approximately $7.9 million today).

Death offers Johnson respect denied in life

Johnson had to ensure that any actions he took to benefit his community were done anonymously. This included funding a local church or helping establish a retirement home, with the donations coming from other relatives.

In Negroland, Margo Jefferson explains that Chicago’s Black elite saw themselves as a distinct “Third Race” during that period.

According to Jefferson, the Black elites viewed themselves as positioned between the masses of Black people and all classes of Caucasians.

The lower classes of Black people were often stereotyped as having loud voices and obnoxious behavior. By distancing themselves from this group, individuals could establish themselves as part of the esteemed colored elite, which included prominent and established families.

Johnson’s bold and vulgar behavior, or his “unsavory reputation and uncouth demeanor,” offended elite black society, prompting him to operate in secrecy due to discrimination.

However, by 1933, his family was considered a “pioneer Chicago family.”

The fate of Johnson’s $250,000 fortune significantly impacts the development of his posthumous legacy.

Johnson’s estate contributed significantly to Black Chicago

In February of 1912, Dora, Johnson’s younger sister, tied the knot with Jesse Binga, who was known as Chicago’s top black businessman.

At the time, it was reported as the most elaborate and fashionable wedding ever held in the history of the African American community in Chicago.

After the marriage, Binga reportedly inherited $200,000 from Johnson’s estate. He invested this money to establish the Binga State Bank, which became Chicago’s first black-owned and operated bank.

Johnson’s impact was evident at the Pekin Theater, which Dempsey Travis described as “the official birthplace of African American theater in the United States.”

Robert T. Motts, the owner of the Pekin, had worked for Johnson in the past and used that knowledge to establish his own gambling establishment, which provided funding for the Pekin.

It has been said that Elijah Johnson, another brother in the Johnson family, utilized their wealth to open the Dreamland Café near Binga’s bank. This café became a popular destination for musicians such as Louis Armstrong, Lil Hardin, King Oliver, and Alberta Hunter, solidifying its reputation as a key venue for showcasing emerging black music throughout the 1920s.

Johnson’s wealth also helped his nephew, Fenton Johnson, an influential poet during the Harlem Renaissance, to succeed.

Johnson’s contributions to his community were finally recognized and respected after his passing.