In the fifth installment of our Illinois gambling history series, we take a closer look at one of baseball’s most notorious scandals: the Chicago Black Sox.

The 1919 World Series marked the debut of national championship play following World War I, sparking unprecedented excitement in the world of baseball. Such was the fervor surrounding the event that officials decided to extend the series to a best-of-nine format, breaking from the customary seven-game tradition.

The Chicago White Sox were heavily expected to win the series against the Cincinnati Reds. However, after nine games, the Reds emerged victorious, leading to speculation of a possible fix.

After the dust had cleared, eight players were handed lifetime bans, altering the landscape of America’s favorite pastime indefinitely.

PART 1: MICHAEL MCDONALD, CHICAGO’S FIRST CRIME LORD

Setting the stage

Low pay, a penny-pinching owner, and increasing interest in illegal sports betting set the scene for scandal

Some quick housekeeping before we start:

It should be emphasized that numerous details of the scandal are still being contested even now.

While a commonly accepted version of the Black Sox saga exists, not everyone agrees with its accuracy. Various conflicting accounts of the events have surfaced, including some from the same individuals. This retelling draws from multiple sources, staying close to the generally agreed upon historical narrative.

That being said, let the saga commence.

The backdrop

Picture it: Chicago, 1919.

The war has come to a close, America is transitioning back to its usual routine, and it can be said that Chicago boasts the top ball team in the major leagues.

Although the team played cohesively, there were underlying tensions among the players. Two factions emerged, one supporting captain Eddie Collins and the other backing first baseman Charles Arnold “Chick” Gandil.

The imbalance in pay was one of the factors contributing to tensions. Professional baseball players, like many others at the time, were paid significantly less than their true value.

The White Sox were divided by low pay issues within the team.

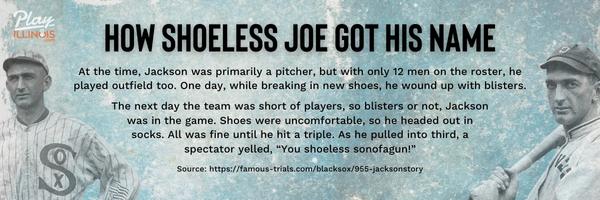

Collins and his educated crew were adept at negotiating favorable contracts, while Gandil and his working-class comrades were disadvantaged without a union. Some of Chicago’s top players, such as Shoeless Joe Jackson and Buck Weaver, earned as little as $6,000 per year ($103,252 today).

No love lost

Regrettably, the league’s reserve clause restricted players from accepting contracts from other teams and transferring without consent from their current team.

This rule provided owners, such as Charles Comiskey of the White Sox, with the advantage of securing players at a low cost.

Comiskey, a former MLB player, was not well-liked by his players due to his reputation for being stingy. It was reported that the one thing the team could all agree on was their disdain for Comiskey.

Although Comiskey may not have been significantly worse than other team owners, he still managed to earn their disdain. He was known for his refusal to have his team’s uniforms laundered, opting to make the players responsible for keeping them clean. Despite the players’ objections, they continued to play in dirty uniforms, gradually becoming more unkempt.

The pigpen mentality persisted until Comiskey had the suits cleaned and deducted the expenses from the players’ salaries.

Another story recounts how star pitcher Eddie Cicotte became frustrated when Comiskey benched him as he was on track for a 30-win season. By sitting Cicotte, Comiskey avoided having to pay a $10,000 bonus, which put financial strain on players and made them vulnerable to corruption. (Adjusted for inflation, that $10,000 bonus would be equivalent to $172,078 in 2022.)

There is also disagreement over whether the scandal that followed was caused by feelings of resentment and difficulty or simply a motivation to make money quickly.

In any case, the true implications would soon be revealed.

PART 2: MONT TENNES, RACE WIRE CZAR

The fix

White Sox players and professional gamblers join forces to throw the series for big bucks

The White Sox, who are underpaid, are on their way to the World Series, and with the increase in illegal sports betting, the stage is set for scandal.

There is disagreement over whether the fix was conceived by a gambler or Gandil himself. Some believe Gandil came up with the idea, while others claim that Boston gambler Joseph “Sport” Sullivan approached Gandil with the proposition.

Nevertheless, it is widely accepted that Gandil was the White Sox player most involved in the corruption scandal. In a 1956 interview with Sports Illustrated, Gandil openly confessed, “I was a ringleader.”

According to reports, discussions about a potential solution began with a select few players, including Gandil, outfielder Oscar “Happy” Felsch, third baseman Buck Weaver, and Cicotte.

Initially, Cicotte was hesitant to join Gandil’s recruitment efforts, but eventually he gave in and became involved in the scheme.

Just days before his first pitch, Cicotte allegedly agreed, “I’ll do it for $10,000 before the Series starts.” In his 1920 grand jury testimony, Cicotte, who had a costly mortgage, elaborated on his decision.

“They pressured me to engage in dishonest activities. I was desperate for money to support my wife and kids. I had invested everything in that farm.”

After securing Felsch and Cicotte, Gandil found it easier to recruit more players. Risberg and McMullin were added next, followed by Williams. The final recruit was Jackson, the team’s top hitter, completing the eight-man squad.

Now all they required was a plan.

Show ‘em the money

Players don’t throw games for free, they expect something in return.

On September 21, eight White Sox players gathered in Gandil’s room at the Ansonia Hotel in New York. Jackson insisted that he did not attend the meeting, a claim that Lefty Williams supported. Despite this, the professional careers of all eight players came to an end.

Gandil provided a detailed description of the Sept. 21 meeting in the 1956 SI article.

All of them were intrigued and believed it was worth investigating to see if the dough would actually be at stake. Weaver proposed that we should receive payment upfront; that way, if things became too risky, we could deceive the gambler, pocket the money, and secure a significant victory in the Series by defeating the Cincinnati Reds. We all agreed that this was a clever strategy.

The next day, Gandil supposedly spoke with Sullivan, informing him that the fix was in place if he could come up with $80,000 ($1,376,698) before the series began. Sullivan responded that providing an $80k advance might not be feasible, but they could discuss it further in Chicago after the regular season.

This is where things start to get complicated. According to Eliot Asinof’s 1963 book on the scandal, another gambler approached Cicotte after hearing rumors of a fix. “Sleepy” Bill Burns allegedly offered to outbid Sullivan’s offer. During a meeting with Burns and Cicotte, Gandil agreed that the group would throw the series in exchange for a $100,000 ($1,720,872) advance.

In his 1922 deposition, Billy Maharg, an associate of Burns, confirmed the story. He stated that originally, they planned to pay $20,000 to each of Gandil, Cicotte, Felsch, Williams, and Risberg.

The sole issue was that he and Burns did not have enough cash readily available for the advance.

Securing the bankroll

Seeking to finance their scheme, Burns and Maharg traveled to New York.

Asinof pointed out that they were approaching Arnold “Big Bankroll” Rothstein, the nation’s most well-known sports gambler.

According to the book, Rothstein was doubtful that the fix would be successful and chose not to participate. Another book by Leo Katcher stated that Rothstein declined because of the high risk involved, with too many people participating and even more keeping an eye on the situation.

According to Asinof’s account, Abe Atell, Rothstein’s trusted associate, seized an opportunity and informed Burns that Rothstein had changed his mind and would provide $100,000.

Meanwhile, Sullivan continued to work on his plans on his own. Unlike Burns and Maharg, Rothstein had a relationship with the experienced gambler and respected him. When Sullivan reached out to Rothstein, Asinof suggests that Rothstein showed a greater level of interest in the plan.

Despite what Katcher believes, it has been reported that Rothstein stated regarding the rumors:

It would be difficult for a girl to prove the paternity of the tenth guy if nine others have also been with her.

According to Asinof, Rothstein made the decision for Nat Evans, a trusted associate, to accompany Sullivan to Chicago to meet the players.

Here, again, complications arise.

Even though there were rumors of gamblers making deals with Black Sox players, there is still no clear agreement on what exactly was agreed upon, even to this day. The true amount earned by each player remains uncertain, with some speculation that in the case of Weaver, he may not have received any payment at all.

The players likely received only $10,000 or less before the series began. The subsequent payments during and after could also be summarized more succinctly.

However, despite this, seven of the compromised players agreed to throw games one and two the day before the opener in exchange for large payouts. Shoeless Joe was the only player not present at the meeting who did not agree to participate.