Jump straight to the content

In the initial part of our Illinois gambling history series, we were introduced to Michael Cassius McDonald, the inaugural crime boss of Chicago.

In the rest of the series, we delve deeper into the individuals, locations, and occurrences that have influenced the current landscape of gambling in Illinois.

Part 2 introduces us to Mont Tennes, who has long been regarded as the United States’ unquestioned leader in the world of gambling.

READ PART 1 OF OUR ILLINOIS GAMBLING HISTORY HERE

Mont Tennes, Chicago’s gentleman gambler

If we were to know every detail of one man’s life, we would have a comprehensive understanding of syndicated gambling as a part of organized crime in Chicago during the first 25 years. This man is Mont Tennes.

Chapter 19 of the Illinois Crime Survey conducted in 1929.

Born in Chicago in 1873 or 1874, Mont Tennes was given the name Jacob at birth. However, his mother affectionately nicknamed him Mont, which eventually became his only public name, distinguishing him from his predecessor, Michael Cassius McDonald, who came to Chicago from New York.

It is said that as a young boy, Tennes showed remarkable skill with dice and other games of chance. By the time he was 20, he had already established his first bookmaking operation. The profits from this venture allowed him to open Tennes Billiard Hall on Lincoln Avenue near Wrightwood in Chicago. Alongside his brothers, who were also his partners in the pool hall, Tennes organized and participated in pool tournaments, often coming out as the victor.

In the subsequent years, Tennes became intrigued by various bookmaking ventures in the Northside and, in 1900, established a chain of saloons. By 1901, he had become well-known among gamblers and critics of gambling, with the latter expressing concern over the deterioration of the neighborhood. Despite the opposition, the success of “Chicago’s gentleman gambler” continued to flourish.

Horse racing was a major factor in his success – Tennes fully embraced the racing world as public interest surged at the start of the 20th century. The sport’s newfound popularity opened up opportunities for gambling entrepreneurs to expand into horse betting from traditional card and table games.

The main issue was that off-track betting hinged on having fast and precise race results. If gamblers found out the outcomes before the house did, there was a high risk of significant losses. Therefore, Tennes’ primary concern became controlling the flow of race information, including track conditions, odds, scratches, and results.

The devil is in the (race) details

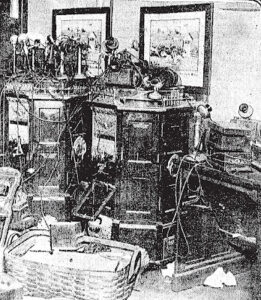

In 1904, Tennes established clearing houses to distribute national race information to bookmaking operations in the city. The first clearing house, located in Dunning just outside the city limits, worked in collaboration with other prominent gambling figures.

Allegedly, observant neighbors became suspicious of the house when they noticed a pair of telegraph lines entering the cottage through a kitchen window.

Tennes persevered with his clearing house, but he required law enforcement protection to ensure the smooth running of the intricate operation.

In order to guarantee his success, Tennes began bribing everyone from beat cops to the chief of police.

In addition to dealing with law enforcement and politicians, Tennes also had to navigate ongoing conflicts with competing bookmakers, some of whom were former associates. The tension escalated when one of his previous partners, who had taken over the City of Traverse gambling boat, had a falling out with Tennes.

As a consequence, Tennes issued a threat to start his own rival gambling cruise, the City of Midland, unless he received a portion of the profits. When the operators of the cruise line declined his demands, it is believed that Tennes attempted to interfere with their operations. However, the disruption, whether caused by Tennes or not, inadvertently caused panic among passengers who mistakenly believed that the boat was on fire.

Despite speculation that Tennes was cut in as an investor, ending the feud in 1906, the subsequent “Gamblers War” suggested otherwise. In the following three years, Tennes and rival gambling bosses experienced physical attacks and over 30 bombings.

Although Smith & Jones were suspected of the scheme, the police were unable to confirm their involvement or even identify the duo. It is more plausible that Tennes was behind the bombings and threats, as he was likely trying to control the dissemination of race-related information in and out of the city.

Additionally, in 1907, authorities successfully shut down the offshore gambling establishment that had been operating for several years.

A race wire czar is born

In 1907, Tennes paid $300 for race information from the Payne News Service of the Cincinnati Daily.

Payne regularly sent race information across the US and Canada, including to Tennes’ Chicago clearing house. But Tennes was unhappy with the high fees charged by Payne. When a mistake in the odds resulted in significant losses for Tennes, he decided to take matters into his own hands. Tennes launched a competing wire service in an effort to push Payne out of the market.

By making that decision, Tennes enlisted representatives to go to races throughout the nation and provide information to his competitor, General News Bureau. Simultaneously, he mandated that all Chicago bookies utilize the new wire service. Those who declined were quickly subjected to bombings or police raids.

Tennes took on Payne in various locations outside of Chicago, peddling his wire service to bookies in San Francisco, San Antonio, Cleveland, Oklahoma City, Detroit, and New Orleans. However, it wasn’t until an explosion rocked John A. Payne’s residence in Kentucky that he finally caved and sold his share to GNS in 1909.

The bombings only began to decrease at that point.

From American gambling czar to charitable retiree

For the following ten years, Tennes maintained his stronghold on racing information in Chicago, across Illinois, and nationwide. Despite facing frequent raids and becoming a target for politicians looking to appear tough on crime, Tennes managed to avoid spending any time behind bars. Much of his good fortune is attributed to his close friend and renowned lawyer, Clarence Darrow.

In 1924, at the age of 51, Tennes decided to retire from bookmaking to dedicate himself entirely to GNS. However, just a few years later, in 1927, he made the decision to sell the news service due to the escalating violence of emerging gangsters. It was rumored that notorious figures like Al Capone and other Chicago-based criminals were becoming increasingly interested in taking control of sporting news. Stay tuned for more on Capone and his activities in future updates.

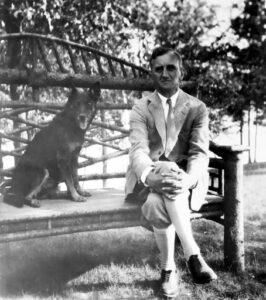

In his final years, Tennes focused on spending time with his children, playing golf, and engaging in charitable endeavors during retirement until his passing in 1941. Following his death, his heirs received a $5 million estate (equivalent to $87,758,620.69 in today’s currency). Tennes also created a $1 million trust aimed at supporting Catholic, Jewish, and Masonic charities, as well as allocating $10,000 each year for Camp Honor, a shelter for troubled boys.

The historic mansion located at 632 W. Belden, constructed in 1885 by Tennes, remains intact to this day. It was last sold in 2012 for $3,050,000. Although currently not listed on the market, Zillow approximates the value of this 5 bedroom, 3.5 bathroom Victorian masterpiece to be at least $2,896,600.